Article de Karl Korsch signé L. H. paru dans Living Marxism, Vol. V., No. 4, Spring 1941, p. 21-29

« Soiled with mire from top to toe, and oozing blood from every pore », a seafaring man emerges on this side of the Atlantic to tell a weird story of intrigue and conspiracy, of spying and counter-spying, of treason, torture, and murder. It is a true story, a reliable record of tangible facts, albeit mostly of facts that remind one of the « stranger than fiction » columns. Yet there is the difference that they are not isolated facts which seem unbelievable only because they do not fit into the common assumptions derived from everyday experience. Valtin’s book reveals a whole world of well-connected facts that retain their intrinsic quality of unreality even after their non-fictitious character has been established. It is a veritable underworld that lies below the surface of present-day society; yet unlike the various disconnected underworlds of crime, it is a coherent world with its own type of human actions and sufferings, situations and personalities, allegiances and apostasies, upheavals and cataclysms.

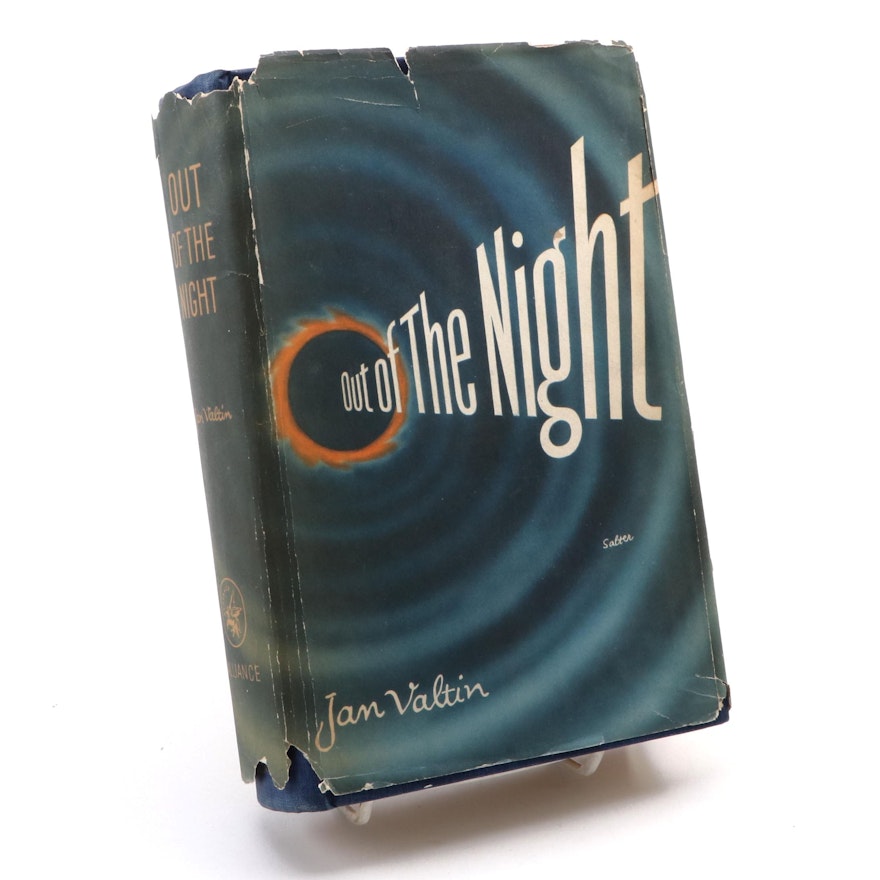

It may well be that the claim of publishers and reviewers that « Out of the Night » is « unlike any other book », and a « mile-stone in the history of literature » is justified, though in quite another sense than theirs. It has probably never happened before that a man of 36 years with « a face of exceptional boyishness » (publisher’s advertisement) has told such a gruesome story, dealing not with his individual adventures but with an important part of world history, not with events long past but with things that happened just the other day and that may still be going on in a very similar way right now.

The title of this book is utterly misleading. Who came out of the night? When and where and for whom did the new day begin? What right have the publishers to claim that this man Valtin is « a symbol of hope in this dark hour, a symbol of a generation which came back from a long trek in the wilderness, to build civilization all over again »? The only thing that his career as an OGPU spy and a Gestapo spy who finally com-muted between both of them as a spy’s spy until even this became utterly impossible might symbolize is the final petering-out in a sort of ambiguous alliance of the competitive fight between German nazism and Russian bolshevism. How many of the readers, who today after fellow-traveling with bolshevism feel elated in the belief that, like Valtin, they have come back from a long trek in the wilderness to build civilization (« defend democracy ») all over again, are aware of the fact that with them, as with their hero, nothing has changed but the external situation? Like Valtin, they never dreamed of the possibility that one day in August, 1939, the two mutually opposed world-powers of fascism and bolshevism would come to terms, after which neither party would need the particular services they had rendered in exchange for that certain amount of « security » or « protection » which in the world as it is, results from the connection with any organization of power — holy or unholy. (This applies to the particular services rendered by professors and other intellectuals just as much as it applies to the services of spies, forgers, killers, and to other menial services.)

On the part of Valtin himself there is not much of an attempt to conceal this woeful state of affairs. In this respect he still towers, despite all we have said and shall say about him, high above some of his fervent admirers within the recently established Defense-of-Democracy Front (formerly « Popular Front ») of the repenting American intellectuals. Although he makes his bow to American democracy — the law of the land of his last refuge — he does not dissemble his essentially different faith. He reveals rather clearly the state of mind that he had reached when after some years of torture in the Nazi concentration camp he finally made a well-prepared gesture of repudiating communism and accepting the program of « Mein Kampf ». He does not pretend that in explaining the reasons for this step to his torturers he was speaking entirely against his true internal conviction:

« Many of the things I said were not lies; they were conclusions I had arrived at in the self-searching and digging which many thousand lonely hours had invited. » (p. 657)

Even now, as an American resident in 1939, he comments on the revolutionary internationalism of his youth in much the same vein as when he had still to prove his recent conversion to « healthy nationalism » to Inspector Kraus in the concentration camp. (pp. 3, 659). Signing the pledge for Nazism. carried conviction because he explained to his torturers that he « joined the C. P. as a boy out of the same motives which brought other youths into the ranks of the Hitler movement. »(657). His preference from the outset, if he had had a choice, might well have been in the direction of the more wholeheartedly violent of the two anti-democratic post-war movements. He faithfully reports the sensation he experienced when as a youth of barely 14 years he, for the first time, « saw a man lose his life ». The man was an officer in field-bray who came out of a station surrounded by mutineers during the revolt of the sailors in Bremen on November 7, 1918:

— « He was slow in giving up his arms and epaulettes. He made no more than a motion to draw his pistol when they were on top of him. Rifle butts flew through the air above him. Fascinated I watched from a little way off. * Then the sailors turned away to saunter back to their trucks. I had seen dead people before. But death by violence and the fury that accompanied it were something new. The officer did not move. I marvelled how easily a man could be killed. — I rode away on my bicycle. I fevered with a strange sense of power. » (p.10)

Similar scenes were to occur again and again throughout the next fifteen years — and though no longer an innocent bystander, he was still invariably watching the scene from a little way off, « fascinated » and fevered with a « strange sense of power. » (There was one glorious exception that will be discussed below.) He was « fascinated » again when in 1931 he heard the first speech of Captain Goering:

— « I tried to be cool, tried to take notes on what I intended to say after Captain Goering had finished, but soon gave it up. The man fascinated me. »** (p. 243)

Thus there is not much of a « gospel for democracy » in this story of an unrepenting adherent of an anti-democratic faith. Valtin’s escape to the country of « democracy » is a mere external occurence. There was no room left for him between the fascist hammer and the communist anvil. He thus symbolizes not the sentimentalized but the real story of those people who, after the German-Russian treaty of 1939 and more particularly after the collapse of Holland. Belgium, France, found themselves in a trap and are still desperately looking for an escape. It is a hypocritical and self-defeating attempt to sell this gruesome but true story of Valtin to the American public as an uplifting report on the redemption of a sinner from the damnation of anti-democratic communism and nazism.

It is equally ridiculous to ask us, as does the January Book-of-the Month-Club News, to believe that this book is « first of all an autobiography and it should be read as such. » The reason that Valtin’s book appeared in this country with the approval of the F.B.I., was the February choice of the Book-of-the-Month Club, has climbed to the top of the non-fiction bestseller list, was advertised on the radio, reprinted in excerpts through two issues of Life and condensed for the March issue of the Reader’s Digest, is not its literary quality but its usefulness as war propaganda against both Nazi Germany and its virtual ally, Communist Russia. We, too, think that the book has merits from a literary point of view. There is a genuine epic quality in the story told in Chapters 18 and 19 (« Soviet Skipper ») and in all parts of the book that deal with ships and harbors and seafaring folk. There is, furthermore, throughout the book an impressive show of that quality of the author’s which impressed even his Nazi torturer when he said to him, « You have Weltkenntnis. » There are other parts of the book, including the pathetic story of « Firelei », which might be said to betray ton much of a lyrical effort; but here the reviewer would like to withhold judgment as it is often difficult to draw a line between genuine emotion and melodramatic display of sentiment. What concerns us, however, is the question of the book’s political importance.

What does it contribute to our knowledge of that great revolutionary movement of the working classes of Europe that threw the whole traditional system of powers and privileges out of balance,— so much so that even in its ultimate defeat it engendered a new and apparently more formidable threat to the existing system — the unconquerable economic crisis, the fascist revolution, and a new world war? What does the book teach us about the mistakes that led to the failure and self-destruction of the revolutionary movements of the last two decades, and what can be learned from it for avoiding similar mistakes in the future?

Before attempting an answer we might consider how much of a contribution to far-reaching political problems we can expect from a book like this. It would be unreasonable to expect much political judgment from a man who was fourteen years old when he was drawn into the maelstrom of the German revolution and later spent the best part of his life in the strict seclusion of the professional conspirator and spy, not counting a three years’ term in an American prison and four years detention in a Nazi concentration camp. Apart from the contacts with real human beings that he gained on shim and in posts on his numerous travels over the seven seas, there was in his long life as a revolutionary just one short period — lasting from May to October, 1923 — during which he had a chance to put in some actual lighting with the rank and file. This period culminated in, and was concluded by, his active participation in the famous uprising of the military organization of the C.P. in Hamburg in October, 1923. Thereafter he left the scene for another period of traveling abroad, performing odd services for the Party, and did not return to Europe and Germany for any length of time until the beginning of 1930. Only then was he charged with more important work under the immediate control of the inner circles of the Comintern; only then did he get a chance to observe events and developments from a point of view broader than that of the secret agent committed to a specific, and for him of ten meaningless task. His misfortune was that the international communist movement had in the meantime lost all of its former independent significance. It had been transformed into a mere instrument of the Russian State. Even in this capacity it no longer fulfilled any political function, but was restricted to organizational and conspiratorial activities. The national units of the Comintern (the C.P.’s of the various countries) had been virtually transformed into detached sections of the Russian Intelligence Service. In name only were they directed by their political leaders; in actual fact they were controlled by the divers agents of the OGPU. Thus, during the first part of Valtin’s career there was a political movement of which he got only the most canted glimpses; and during the latter part, all that was left of the former political character of the C.P.’s was a mere semblance and pretence of a genuine political movement.

This summary of Valtin’s personal history explains both the usefulness and the shortcomings of his contribution to the political history of the revolution. He does not understand much, even today, of the very different character that the communist workers’ movement in Germany and in other European countries showed in its earlier phases; he accepts its later conspiratorial character as the inevitable character of a revolutionary movement. Such a tragic misunderstanding results, in his case, from a peculiar conjunction of different causes. His extreme youth during the formative phase of the Communist Party, 1919-1923, the particular conditions along the « water-front » and more especially in Hamburg, that in many ways anticipated a much later phase of the general development of the Party, his own impetuous, enthusiastic, reckless nature that from the outset designed him for the role of a « professional revolutionist » in the Leninist sense of the term, his particular usefulness as a « real sailor » (p. 107) in a field that was of outstanding importance both for international revolutionary politics and for the specific aims of Russian power politics:— all this contributed to deprive him of his full share in the « normal » experience of the class struggle long before the split between the masses of workers and a secret inner circle became a typical feature of the communist movement all over the world. When he joined the party in May, 1923, he was at once singled out for « special » duties as a member of one of the « activist » brigades in the harbor of Hamburg, as a military leader, and as a « courier » for the exchange of messages between the known leaders of the German party and their Russian military advisers. It was by sheer instinct and good luck that he did not get involved in the first amateurish activities of the terror groups that were then introduced into German revolutionary politics by the secret agents sent from Russia for this purpose.

It is easy to show how little Valtin really understood of the daring ambiguities of the Russian « communist » interference in the revolutionary struggle of the German workers. To this day he believes in most of the romantic stories that were then whispered from mouth to mouth about the various important « generals » who had been secretly sent by the Soviet government to handle the military end of the planned insurrection. It is true that a number of Russian officers had been sent, that they had advised the German Party leaders, and that they were, in fact, responsible for such fantastic schemes as that of the assassination of General von Seeckt, head of the German Reichswehr, by the T.-groups of the ill-famed Felix Neumann, who later betrayed the whole crew of the T.-units and their secret leaders, the Russian officers, to the German police. But it is equally true that the Russian officers had come to Germany in a double capacity. While the Soviet government was assisting the German C.P. in preparing the insurrection, it was at the same time engaged in secret negotiations with the same General von Seeckt whom its Tchekist emissaries planned to assassinate. These negotiations with the militarist and reactionary clique — the fore-runners of Nazism in the Weimar Republic — were conducted with a view to preparing a Russo-German alliance against France and England. who had at that time invaded the Rhine and Ruhr territories of Germany. The negotiations led to a number of military agreements and paved the way for the treaty that was actually concluded between Germany and Russia in the spring of 1926.

All the Russian officers who had been tried and sentenced to death penalties and long prison terms in the so-called Tcheka-trial at Leipzig in 1924, were shortly afterwards returned to Russia. The underlying diplomatic procedure was screened by the arrest and trial of a few otherwise unknown German students by the GPU in Moscow on the charge of espionage. They were convicted and afterwards exchanged for « General » Skoblevsky (alias Helmut, alias Wolf) and the other Russian officers captured in Germany. In reporting his version of these events, Valtin still naively believes in the story which was then spread by the German and Russian governments and was at the time widely accepted by the workers. Felix Djerjinsky, the « supreme chief of the GPU », he tells us, had silently inaugurated the drive against the German students and thus compelled the German authorities to return the Russian officers who had plotted against the life of von Seeckt and had nearly succeeded in organizing a revolutionary overthrow of the German state.

We have discussed this particular question at length not for the purpose of exposing the naivity of Valtin’s report, but for a more important end — namely, to show the distortion that the whole history of the class-struggle undergoes if it is regarded from the restricted viewpoint of the technical « expert », the professional conspirator and spy. This distortion is inherent in the whole of Valtin’s report on those earlier phases when the communist movement was still to a greater or lesser extent a genuine political movement, a true expression of the underlying class-struggle.

Unfortunately, the same objection cannot be raised against Valtin’s report on the later phases of the communist movement. By that time the distortion of a genuine political movement to a mere conspiratorial organization had become a historical fact: After 1923 and again after 1928, 1933, and ultimately after 1939, the so-called Communist Party became what Valtin assumed it had been at all times — a mere technical instrument in the hands of a secret leadership, paid and controlled exclusively by the Russian State, entirely independent of any control by its membership or by the working class at large.

Thus the greater part of Valtin’s book presents a most valuable description of the real distortions that must befall a revolutionary movement that becomes estranged from its original purpose and from its roots in the class-struggle. There is no doubt that Valtin has given a realistic description of this historical process and of its ultimate outcome. He has presented the facts without reserve, with no perceptible sparing of other persons and very little sparing of himself. He has recorded the characteristic features of persons. events, and localities with a rare gift both of memory and of accurate detailed description. He has thus revealed the complete inside story of an immense plot, whose details — by a carefully devised and rigidly observed procedure — were known only to a minimum number of immediately involved persons, most of whom have died in the meantime without recording their memories. Thus in his factual report he traces to the bitter end the working of one of the processes that contributed to the utter defeat of the most revolutionary movement of our time and to the temporary eclipse of all independent workers’ movements in a twilight of despair, loss of class-consciousness. and cynical acceptance of the counter-revolutionary substitute for a genuine workers’ revolution.

Yet it cannot be said that Valtin has presented the story of the degeneration of the communist movement in a manner in which it would be most fruitful for the politically interested among his readers. We must supplement his tale with two additions. We must point out the subtle process by which the first germs of the later decay were introduced into the revolutionary movement; and we must try to understand the whole of the historical development that from those inconspicuous beginnings led to the present complete corruption of a once-revolutionary movement.

Little did the masses of the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany know what they were in for when at their convention in Halle in the fall of 1920 they accepted, along with twenty other « Conditions of Admission to the Communist International », the necessity for a secret « illegal activity’ in addition to the regular activities of a revolutionary party. They had had some experience in « illegal action » during 1914-18. They had built up a secret organization of Workers’ Councils, and ultimately, of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils to end the war and to organize the socialist revolution. They had become used to periods when all legal activities of the revolutionary parties (outside of the still formally respected parliamentary sphere) were suppressed, their leaden persecuted, their institutions destroyed and thus, for a certain time, the whole party « forced into illegality ». Thus they imagined that nothing was at issue in the 1920 discussion but this indispensable element of any genuine revolutionary action — an element that is present even under the most normal conditions of the class struggle (e. g., in the organization of an ordinary strike). They suspected the right-wingers who opposed all the twenty-one conditions of a malicious plot against this inevitable form of maintaining the revolutionary movement through the critical periods immediately preceding its decisive victory or following its temporary defeats. They were for this reason unable to listen to the warnings of the left-radical communists who, adhering to the tradition of Liebknecht and Luxemburg. emphasized the spontaneity of revolutionary mass action from the bottom up as against the supremacy of an uncontrolled leadership from the top down. They did not, and from their historical experience could not, anticipate the fact that from then on a steadily increasing part — and ultimately all of their organization and politics, tactics and strategies, their choice of foes and allies, their theoretical convictions, language and mores, in fact the whole of their behavior — would depend on secret orders received from the often suspicious agents of unknown superiors without the slightest possibility of influence or control on the part of the members, (This is what became known in communist circles by the beautiful name of « democratic centralism »).

Already in the next year, the « March-putsch » of 1921 gave a first impression of the disease that from then on was to destroy the healthy growth of the revolutionary movement of the German workers. It was the first of a long series of events in which the elite of the most valiant and the most devoted workers was sacrificed for an insane enterprise that was not based an a spontaneous movement from below nor on a critical condition of the existing economic and political system. It was planned, and led to defeat, entirely by a secret semi-military organization. The same game was repeated under similar conditions, and invariably with the most destructive consequences, through all subsequent phases until it actually fulfilled the ultimate purpose that had been inherent in the procedure from the outset. It was used not to arouse the workers, but to restrain them from the decisive fight against the advancing forces of Nazism because (as Manuiilsky said at the Eleventh Session of the Executive Committee of the Comintern in 1932): « It is not true that Fascism of the Hitler type represents the chief enemy ». When this was said, however, the conspiratorial idea of the revolution had already nearly run its full course, although an aftermath was still to come. The period of the so-called Popular Front, inaugurated after 1933, brought many new phases until the Communist Party reached the utter debasement which is illustrated by the « communist » staff member of the City College of New York who was so conspiratorial that in helping to edit and put out the Communist campus paper he wore gloves in order to prevent his leaving fingerprints, because he had « an inordinate fear of detection. »***

A final objection that might he raised against Valtin’s picture of the degeneration of the Communist Party is that he does not discuss the manner in which Lenin’s concept of the conspiratorial revolution is closely related to other parts of Lenin’s theory—namely, to his concept of the party and the state, to his assumption on the role of the various classes, and even of whole nations, in the « uneven development » of the proletarian revolution and, last not least, to his theory of the « dictatorship of the proletariat ». Here again an apparent shortcoming of the book is due less to the restricted technical outlook of the author than to the fact that none of those wider political concepts of the Leninist theory exerted the slightest effect on the action and omissions recorded in his hook. During those later phases of the Comintern to which his report is mainly devoted, all the high-sounding terms of the original theory had long since degenerated into empty phrases without any bearing on the practical behavior of the « revolutionary » conspirators All that the people described by Valtin needed of those Leninist theories was the cheerful acceptance of an unrestricted use of all forms of violence both against the existing powers and against those proletarian critics of an assumedly infallible leadership who had been described by Lenin and were described up to the end in ever new and more poisonous terms as the « agents of the bourgeoisie within the ranks of the proletarian class », the « agents of the counter-revolution », of « Social-Fascism », of « Trotskyism », etc.. etc.

There was no longer any connection between the various forms and degrees of violence applied and the different tasks to be solved at the different stages of the revolutionary development. In fact, Valtin’s uncritical report could be used to demonstrate an inverse relation by which the use of violence became the more unrestricted the more the movement lost its original revolutionary character and became a mere intelligence service at the command and in the pay of the external and internal power politics of the Stalin government in Russia. For example, an indiscriminate use of sabotage had been repudiated by the early communists in accordance with all other Marxist parties. In the later phases, as is most impressively revealed by Valtin, all conceivable forms of sabotage were commonly used and had long ceased to involve any theoretical problems. Again the famous « purge » of non-conformist party members was applied originally in the form of disciplinary measures culminating in expulsion from the party; it was later developed into methodical character-assassination and, ultimately, into outright assassination of individuals and whole groups, party members and non-members, both inside and outside Russia. (The murder of Trotsky by the GPU in Mexico was only the most conspicuous example of an almost « normal » procedure that scarcely interested a wider public as long as it was restricted to the extinction of present or former revolutionists).

In conclusion, one word against those inspired people who want to minimize the significance of Valtin’s book by pointing out that the author was never « an important communist ». It is indeed remarkable that this most ferocious attack against the present-day usurpers of the name of revolutionary communism should have come, not from one of the people high up in the party, but from one of those ordinary workers who were forever misused and sacrificed for the higher purposes of the gods. Here is a fitting symbol of the form in which the last stroke against the counter-revolutionary power entrenched in Stalin’s Russia is bound to come:— the rebellion of the masses.

L. H.

*) Emphasis by reviewer.

**) Emphasis by reviewer.

***) See the testimony of Mr. Canning in the New York Times of March 3rd. 1941.